We’ve been looking at atonement theories over the past few weeks: When Jesus Died – A Conversation on Atonement, Wonder-Working Pow’r, and A Soothing Aroma.

The big question is: how do we understand/interpret Jesus’ death? This might seem a merely academic debate that should stay behind church doors between some old, dusty theologians. But I’m interested in the issues because there are societal and cultural realities that are shaped and guided by certain theological views – and this impacts all of us, whether we are people of faith or not. Today we are drawing from two books that seek to show how certain atonement views have helped to shape the world we live in. First up, J. Denny Weaver’s The Nonviolent Atonement:

Atonement theology starts with violence, namely, the killing of Jesus. The commonplace assumption is that something good happened, namely, the salvation of sinners, when or because Jesus was killed. It follows that the doctrine of atonement then explains how and why Christians believe that the death of Jesus—the killing of Jesus—resulted in the salvation of sinful humankind.

In much of the world generally and in the United States in particular, the prevailing assumption behind the criminal justice system is that to “do justice” means to punish criminal perpetrators appropriately. “Appropriately” means that the more serious the offense, the greater the penalty (punishment) to be imposed, with death as the ultimate penalty for the most serious crimes.

There is a pervasive use of violence in the criminal justice system when it operates on this belief that justice is accomplished by inflicting punishment. Called retributive justice, this system assumes that doing justice consists of administering quid pro quo violence—an evil deed involving some level of violence on one side, balanced by an equivalent violence of punishment on the other. The level of violence in the punishment corresponds to the level of violence in the criminal act.

Satisfaction atonement assumes that the sin of humankind against God has earned the penalty of death but that Jesus satisfied the offended honor of God on their behalf or took the place of sinful humankind and bore their punishment or satisfied the required penalty on their behalf. Sin was atoned for because it was punished—punished vicariously through the death of Jesus which saved sinful humankind from the punishment of death that they deserved—or because the voluntary death of Jesus paid or satisfied a debt to God’s honor that sinful humans had no way of paying themselves. That is, sinful humankind can enjoy salvation because Jesus was killed in their place, satisfying the requirement of divine justice on their behalf. While the discussion of satisfaction atonement involves much more than this exceedingly brief account, this description is sufficient to portray how satisfaction atonement, which assumes that God’s justice requires compensatory violence or punishment for evil deeds committed, can seem self-evident in the context of contemporary understandings of retributive justice in North America as well as worldwide systems of criminal justice.

In other words, our theology (our view of God) shapes our sociology and public policy (our view of each other, and how to live together).

Not convinced yet? Keep reading. The following is taken from Ted Grimsrud’s new book, Instead of Atonement: The Bible’s Salvation Story and Our Hope for Wholeness, published by Wipf & Stock in 2013. Grimsrud shows how certain theological views (especially God’s response to human sin) came to shape political realities, in particular, crime and punishment:

Justice became a matter of applying rules, establishing guilt, and fixing penalties—without reference to finding healing for the victim or the relationship between victim and offender. Canon law and the parallel theology that developed (in the early Middle Ages) began to identify sin as a collective wrong against a moral or metaphysical order. Crime was a sin, not just against a person, but against God, against God’s laws, and it was the church’s business to purge the world of this transgression. From this understanding of sin, it was a short step to assume that since the social order is willed by God, crime is also a sin against this social order. The church (and later the state) must therefore enforce order. Increasingly, focus centered on punishment by established authorities as a way of doing justice.

By the end of the sixteenth century, the cornerstones of state justice were in place in Europe, and they drew deeply from the underpinnings of retributive theology. New legal codes in France, Germany and England enlarged the public dimensions of certain offenses and gave to the state a larger role. Criminal codes began to specify wrongs and to emphasize punishment.

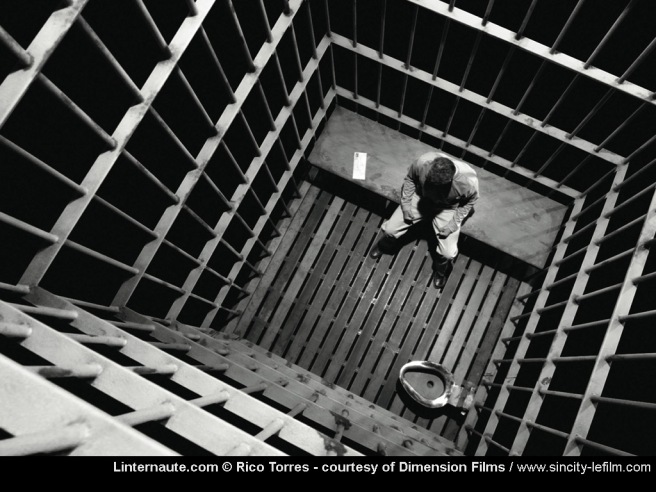

The primary instrument for applying pain came to be the prison. Part of the attraction of prison was terms that could be graded according to the offense. Prisons made it possible to calibrate punishments in units of time, providing an appearance of rationality in the application of pain.

Between the mid-1800s and the 1970s, the practice of criminal justice in the United States evolved away from strictly retributive justice. David Garland, in his important book, The Culture of Control, argues that the “penal-welfare” model gained ascendancy among criminal justice professionals, with a concern for rehabilitation of offenders and a diminishment of focus on strict punishment. This model, however, never received widespread support among the general population. Because politicians for a long time found it disadvantageous to try to intervene in criminal justice issues due to conventional wisdom that criminal justice was a no-win issue to be identified with, the prison system was allowed to pursue its own agenda.

However, with a significant increase in the crime rate in the United States after World War II, politicians discovered that “law and order” rhetoric actually gained them popularity. (See the documentary: The House I Live In [streams free online or on Netflix] for more on how Nixon and Reagan especially used this rhetoric, culminating in the “War on Drugs”).

The logic of retribution that became embedded in our criminal justice practices by the nineteenth century, even though it was mitigated against somewhat during the penal-welfare era, has returned with a vengeance in the last quarter of the twentieth century and the early years of the twenty-first. As summarized by legal scholar William Shuntz, “No previous generation of Americans embraced the version of retributive justice that has held sway in the United States over the past thirty years… Only in the last decades of the 20th century did most American voters and the law enforcement officials they elect conclude that punishing criminals is an unambiguous moral good. The notion that criminal punishment is a moral or social imperative—the idea that a healthy criminal justice system should punish all the criminals it can—enjoyed little currency before the 1980s.” In the retributive model of justice, crime has come to be defined as against the state, justice has become a monopoly of the state, punishment has become normative, and victims have been disregarded.

Going back to the Middle Ages, penal theory helped reinforce the punitive theme in theology—e.g., a satisfaction theory of atonement that emphasized the idea of payment or suffering to make satisfaction for sins. Retributive theology, which emphasized legalism and punishment, deeply influenced Western culture through rituals, hymns, and symbols. An image “of judicial murder, the cross, bestrode Western culture from the 11th to the 18th century,” with huge impact on the Western psyche. It entered the “structures of affect” of Western Europe and “in doing so, . . . pumped retributivism into the legal bloodstream, reinforcing the retributive tendences of the law.” The result was an obsession with retributive themes in the Bible and a neglect of the restorative ones—a theology of a retributive God who wills violence.

The paradigm of retributive justice that dominates Western criminal justice is a recipe for alienation. By making the “satisfaction” of impersonal justice (or in theological terms: “God’s holiness”) the focus of society’s response to criminal activity, the personal human beings involved—victims, offenders, community members—rarely find wholeness.

Moreover, the larger community’s suffering only increases. Instead of healing the brokenness caused by the offense, we usually increase the spiral of brokenness. Offenders, often alienated people already, become more deeply alienated by the punitive practices and person-destroying experiences of prisons.

Garland portrays our “culture of control” in criminal justice as a new form of segregation. We focus on on rehabilitating and reintegrating offenders, but on identifying and isolating offenders. “The prison is used today as a kind of reservation, a quarantine zone in which purportedly dangerous individuals are segregated in the name of public safety.” That this “segregation” has a decided racial aspect in the United States is confirmed in Michelle Alexander’s powerful book, The New Jim Crow. (This one is a must read!!!)

Present dynamics emphasize the difference between offenders and law-abiding citizens. Garland writes, “being intrinsically evil or wicked, some offenders are not like us. They are dangerous others who threaten our safety and have no call on our fellow feeling. The appropriate reaction for society is one of social defense: we should defend ourselves against these dangerous enemies rather than concern ourselves with their welfare and prospects for rehabilitation.”

James Gilligan, former director of psychiatry for the Massachusetts prison system, draws on his experience working closely with violent offenders to critique retributive justice in our criminal justice system. “A society’s prisons serve as a key for understanding the larger society as a whole.” When we look through the “magnifying glass” of the United States prison system, we see a society focused on trying to control violence through violence, a society that willingly inflicts incredible suffering on an ever-increasing number of desperate people.

There is much more to be said, of course, and these are complicated matters with many causes and effects. A few questions in closing:

- Are you surprised at the possible connection between atonement theologies and criminal justice practices? Do you think it’s a legitimate connection?

- Can you think of other ways to view forgiveness and wholeness that breaks out of the crime/punishment narrative? Are there biblical texts that support your view?

- What other questions are on your mind regarding atonement issues?

I just wanted to thank you for the well thought out essay. Yes, you are right about how atonement issue can distort reality.

For example, any time some one is accused of an occurrence, that person is immediately thought of as guilty until proven innocent, which is not easy to do, as the cards are already stacked against you by an angry, damaged, uninformed crowd who is ready to cast stones first, and ask questions later. (Kudos for Sandy, above, for getting it!)

Look at the example of Christ, who was well aware at all times that he was under scrutiny, and being accused for helping his fellow man, and his work was being distorted and altered by the Pharisees who were exceedingly jealous of Christ’s ability to lead and offer to relief to the people. Caesar didn’t care for justice, he just wanted the pressure of himself.

I huge issue is that many times the accused is there merely for public display, a scapegoat for a damaged society and governmental leaders who need to appear that they are doing something because they are too afraid to provide real leadership to a very needy public. Many times it is an innocent that is punished, and the true perpetrator slinks off, scott free to continue the damage.

It is very difficult to find someone who is actively searching for answers, as many just want to sweep injustice under the rug. Again, thank you for getting people to at least look at what some of the issues are, so perhaps someone, somewhere can make changes towards true justice/healing.

LikeLike

A couple of thoughts prompted by this.

I have never really understood how punishing an innocent man for someone else’s crime can be considered justice, at least in a crime & punishment context.

On the other hand debts and debt-based slavery can be redeemed by anyone willing to pay the price.

Similarly contract law (as opposed to criminal law) works on a more abstract ‘penalty’ basis: there is a set fine for a given infringement and it doesn’t really matter who pays that. The Jewish legal system, based on Torah, was, of course, contract law, a covenant, not criminal law; cf Deut 28 and Deut 30:11-20, for example.

As I understand it Roman law at the time was much more based around the idea of crimes being against the state, or against society, and on the importance of deterrence: crucifixion and decimation (killing one in ten, chosen by lot) being examples.

I wonder if a Roman approach to law and punishment has shaped the church’s understanding of Jesus’ crucifixion far beyond any reasonable understanding of the texts. It is surely far easier to shape our reading and understanding of Scripture to fit in with our existing beliefs than it is to reshape our beliefs.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Prayerful Anglican.

LikeLike

Spending most of my adult life as a Christian, I didn’t begin to question this idea of violence until I began to think about it aside from what I had been taught. If violence is violence, then can it be justified even in the name of God? Christ’s satisfaction atonement is still rooted in violence, a violent act perpetrated against an innocent man. Sometimes I wonder, does that make sense, coming from a loving God? I can definitely see how this connection can set the stage for our modern ideas of retributive justice, and there is no doubt racism is being continued in the veiled name of this theory of justice.

This post has definitely made me think. So many questions, but ones we definitely need to ask and discuss.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on A Pastor's Thoughts and commented:

The thoughts in this article are worth some consideration. I don’t present it as end all, but a platform for disussion.

LikeLike

‘Crime and Punishment’ – I hated that book! Put me off Dostoyesvsky for life. Ugh. With regard to the criminal justice system (I am from the UK and our system differs but is broadly the same), as someone who has been the victim of crime which left *me* with a life sentence, and who also experienced the perpetrators getting away with it, speaking on behalf of victims of crime like myself, I think there has to be some element of punishment involved because the perpetrator and the culture must recognise the deep scars that the victim is left with. I had the unpleasant discovery that ‘not guilty’ is not the same as ‘innocent’ – it can mean that there was not enough evidence (so the more cunning a criminal is, the less likely they are to be punished). It is all a big mess and I’m praying over whether I sue the police who were negligent in their duties 😦

BUT as a Christian I am called to love my enemies and to pray for them. This I take seriously. I would rejoice if I thought that those men had genuinely repented and turned their lives to Christ. Maybe not ‘rejoice’. I would be glad, though. Because sin is sin. And God forgives all sin. That said, while we must keep dangerous people off the streets, for the sake of society at large, we must also promote rehabilitation. Given that redemption is arguably the message of the entire bible, this is hardly a novel idea. Rehabilitation must mean helping people to value themselves and to begin to make the right choices for themselves. So often damaged people make damaged choices because they don’t recognise how or why they make choices, or even that they have certain choices. It’s the same as addiction. That is *not* a liberal lefty wipe-their-arses wishy washy idealism, either, I’m by no means naive! No. You have to be incredibly firm, but also give support to those who want to change.

LikeLike